Beyond Food Banks: The Book of Ruth, SNAP, & Social Responsibility

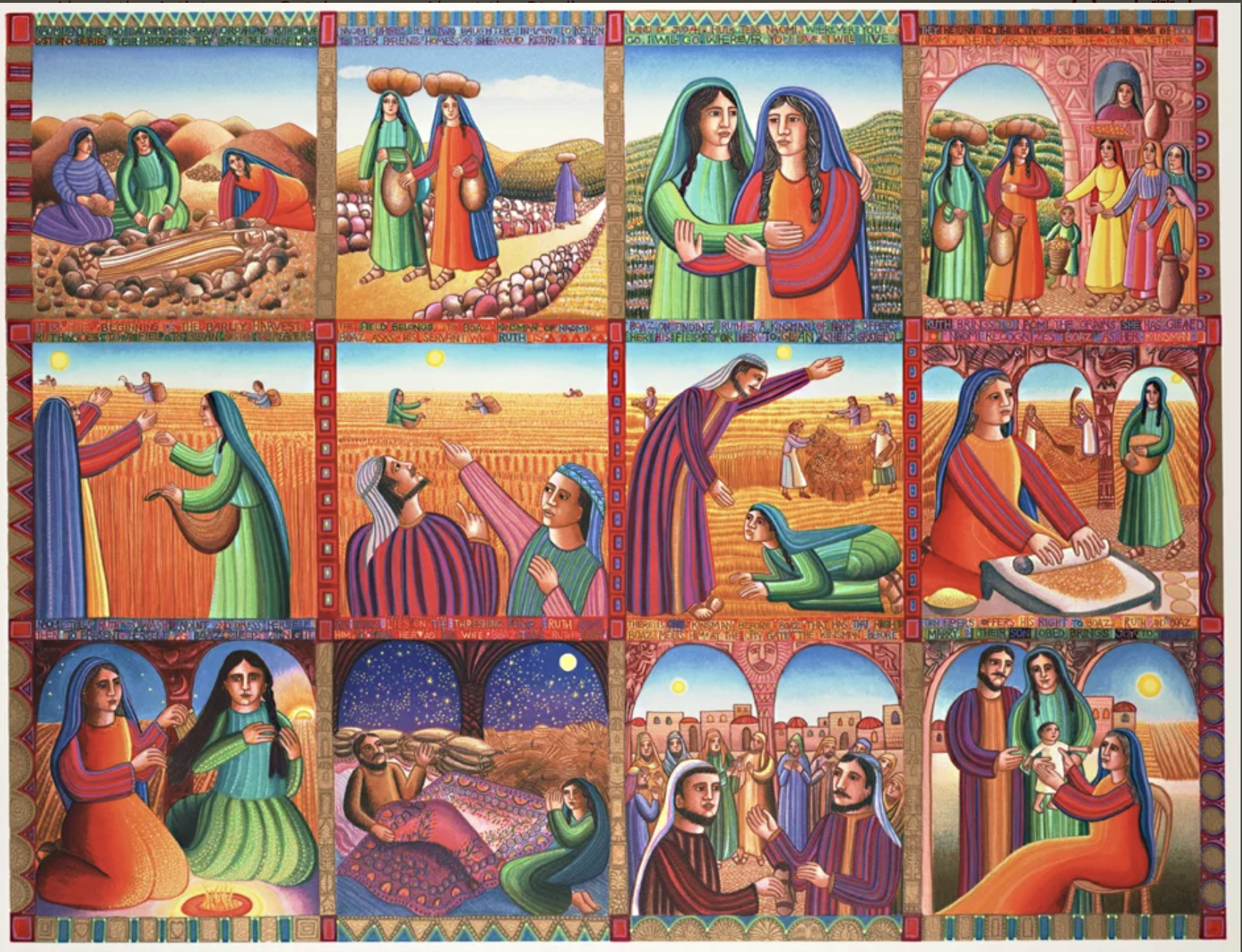

Story of Ruth, John August Swanson

Famine & Immigration in Ruth

The Book of Ruth opens with a famine in the land of Judah, which drives Elimelech, his wife Naomi, and their two sons from Bethlehem in Judah to the land of Moab. Their sons take Moabite wives, which was a major violation of Jewish custom and scripture because Moab was the enemy of Israel and Judah. Not long after they arrive in Moab, Elimelech dies.

Then both of Naomi's sons die, leaving these three women—Naomi, Orpah, and Ruth—widowed and vulnerable. A woman’s wellbeing in this patriarchal society came from the male head-of-household she was a part of—her father’s house, her husband’s house, or her sons’ house.

Naomi has no other choice but to leave Moab and return to Judah in hopes that one of her kinsmen would take her in. She tells her two daughters-in-law to return to their kinsmen in Moab. Reluctantly, Orpah leaves, but Ruth is defiant. She remains with Naomi—an act of radical loyalty and courage.

SNAP in the Ancient World

In chapter 2, Naomi and Ruth return to Naomi’s kinsmen in Bethlehem, but it seems as though they’re still struggling because they enroll in SNAP. Back then it was called it gleaning, but it was no doubt a Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program prescribed by scripture. Leviticus 19—an oft-quoted chapter of the Bible (for all the wrong reasons)—says:

When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap to the very edges of your field or gather the gleanings of your harvest. You shall not strip your vineyard bare or gather the fallen grapes of your vineyard; you shall leave them for the poor and the alien: I am the Lord your God.

In other words: don’t hoard your abundance—leave some behind for those who need it so that everyone has enough.

Ruth gleans in the fields. And she happens to glean in the fields of Boaz, an affluent relative of her deceased father-in-law. And Boaz happens to see this unfamiliar woman gleaning in his field. When he discovers who she is, he commends Ruth for her faithfulness to Naomi, which he’s heard about. He feeds her, ensures she’s safe, and allows her to return to his fields.

Generosity & Responsibility

You’d be hard pressed to find a story that speaks more powerfully to the moment we’re in right now than the Book of Ruth. Ruth isn’t just an ancient story—it’s our story, Pádraig Ó Tuama reminds us. Because Ruth is the story of an immigrant family crossing borders—leaving everything behind and taking great risks—in search of safety and a better life. Because Ruth is the story of families who know what it’s like to go hungry.

And it’s also the story of a community caring for the poor and the immigrant—for their neighbors—not just out of individual concern, not just out of personal generosity, but out of a sense of social responsibility.

Obedience to the biblical command to practice gleaning (still practiced in some parts of the world today) was a communal safety net created by a responsible society. It didn’t leave the care of the most vulnerable to the whims of a few.

When Generosity Isn’t Enough

Generosity is great. We love being generous, but we struggle to be responsible. When I’m generous, I’m in control. I decide when I help my neighbor, how I help my neighbor, and how much I help my neighbor.

It’s more about me and my needs. It’s more about making myself feel good than it is about my neighbor and their needs. It assumes no responsibility, no duty. Generosity is important. But generosity without social responsibility becomes a way to feel better without creating any meaningful change in society.

Governor Lee has been incredibly generous—he’s directed $5 million in grant money to food banks across our state. Never mind the fact that it doesn’t come close to touching the $72 million needed by Tennessee’s families this month to replace their SNAP benefits. Never mind the fact that the Governor has $2.2 billion with a B at his disposal in the state’s Rainy Day Fund. A $5 million grant is generous. But it isn’t responsible because it isn’t just. It’s throwing crumbs to thousands of hungry families. It’s not just our state government, of course. Our federal leaders are also failing to feed hungry people during this shutdown.

And, if we’re honest, maybe there are times when we prefer generosity over responsibility because we want to be in control. We don’t want anyone telling us how to spend our money, by God. This is America, after all. No one can tell me what to do—not the government, not the community, not the church.

Response-Ability

Generosity is wonderful. And I hope we’re all generous and donate to our food banks during this crisis. But the socially responsible thing, the morally responsible thing, the just thing to do is to fund SNAP.

And the responsible thing for us to do is to make time to contact the Governor and our state legislators and demand that we feed hungry people in our state while the federal government sorts out SNAP as it reopens. This isn’t just a “poor person’s problem.” That’s often the narrative, and that’s why these problems persist.

This isn’t just a poor person’s problem because we’re “caught,” Dr. King says, “in an inescapable network of mutuality. [...] Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” We’re caught—we’re trapped together, for better or worse.

I never thought that providing a basic safety net for the most vulnerable would be up for debate. But, then again, I never thought I’d hear that empathy was “toxic.” Who knew that basic human decency would become so radical?

The Gospel Call: From Generosity to Justice

The gospel calls us to something deeper than generosity—it calls us to justice. I am grateful for the prophetic food justice work of Gordon Bonnyman and the Tennessee Justice Center among many others. I challenge you—us—to use our voices to advocate for SNAP beneficiaries. People are going hungry while the government reopens and gets these major systems back on track.

And I challenge us to shift out of a generosity mindset and toward a community care mindset—a gospel mindset that believes our neighbors’ flourishing is bound up in our own. We are responsible for one another and to one another.

May we build a more just community where no one goes hungry; where no one has to choose between food or healthcare. The work for that vision must continue.